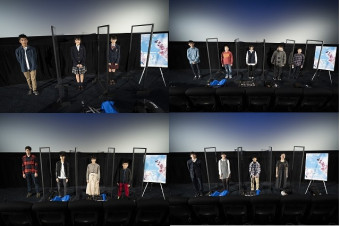

An appreciative audience was on hand for the screening of the 4K digital restoration of Hiroshi Inagaki’s acclaimed 1943 film The Rickshaw Man (Muhoumatsu no issho) on November 4, playing in the Japanese Classics section of the 33rd Tokyo International Film Festival. It was paired with a short but illuminating documentary about the restoration by Ema Ryan Yamazaki, Wheels of Fate: The Story of the Rickshaw Man, and followed a Q&A session with cinematographer and restoration consultant Masahiro Miyajima, director Ema Ryan Yamazaki, producer Eric Nyari and executive producer Masakazu Itsukage.

Directly translated as “The Life of Matsu the Untamed,” The Rickshaw Man is a powerful portrait of the decency and strength of the average man, and was praised by film historian Donald Richie as “the finest of the wartime films with a Meiji setting.”

Set in the city of Kokura, Kyushu at the turn of the 20th century, the story revolves around Matsugoro, a crude and violent rickshaw man played by Tsumasaburo Bando, who one day helps a young boy after he falls and finds his life changing. He wins over the rest of the boy’s family, including his mother (played by Keiko Sonoi) and military officer father, and when the father passes away from a sudden illness, Matsu devotes himself to supporting the boy and his mother in whatever way he can, from fixing broken kites to giving swimming lessons in public baths.

Legendary cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa captures the city and inhabitants of Kokura with his trademark lyricism, effortlessly transitioning between the different energies of sports tournaments, lantern festivals, street brawls, and the spinning wheels of Matsu’s rickshaw, a motif that frames the passing years of his life and, ultimately, sacrifice.

Inagaki’s masterpiece is the rare film to be heavily censored by both Japanese wartime government and post-occupation US forces, due to what were perceived as transgressions against the Japanese military as well as sympathies towards Japanese militarism. Yamazaki’s documentary about the restoration of the film reveals that Inagaki himself made the cuts, which included several elaborate montage sequences and scenes suggestive of Matsu’s romantic feelings towards the officer’s widow.

This censure by both authorities might be the strongest testament to the film’s universal humanism, a generosity of the human spirit that stood in contrast to the era’s fervent militarism. The restoration was commissioned through Kadokawa Film Company and the Martin Scorsese Film Foundation.

Masahiro Miyajima was hired as a consultant since he had served as Miyagawa’s assistant on the film. During the Q&A he described the experience as “like working with God.” Miyajima vowed to complete the restoration while he was still alive in tribute to his master, and Yamazaki’s documentary shows how he recreated storyboards based on Miyagawa’s shots in the film.

On discussing how he had to earn Miyagawa’s respect, Miyajima said, “He never called you by name when you were starting out. He just called you ‘bon,’ (“boy” in Kansai dialect). But once you learn the job, he called you by your name.”

The Miyagawa family were also involved in the restoration, along with professionals in New York, Portugal and Japan, who had to communicate virtually during the coronavirus pandemic. Yamazaki likened their task to what the filmmakers might have experienced during wartime: “I was able to really understand their strong determination to make something deeply humanistic and against the current of the times.”

The film’s tragedy did not end at its edited content; Keiko Sonoi, who plays the boy’s mother, died of exposure to radiation following the Hiroshima atomic bomb. A Takarazuka Revue performer and member of the Sakura-tai traveling shingeki troupe, Sonoi only had one film credit, but it was a role that Yamazaki believed she was born to play. “Knowing the tragedy that befell her gives her role in the film an ephemeral quality,” said the director. “But you can still sense her presence and how she holds her own with such a big star like Tsumasaburo Bando.”

Fans and family members of the filmmakers were in attendance, including the sons of Inagaki, Miyagawa and Bando, as well as the animator Taku Furukawa, who provided the animated re-enactments featured in Yamazaki’s documentary. “This is a 77-year old film and was in terrible shape,” explained Miyajima, “but everyone put in their best effort and I think we made something worthwhile.”