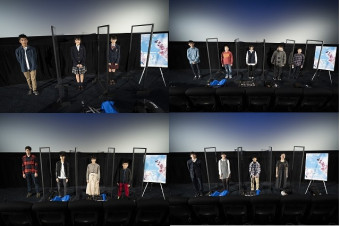

Actor Naoya Makoto (Himitsu Sentai Gorenger), writer Naruhisa Arakawa (Kaizoku Sentai Gokaiger), directors Katsuya Watanabe (Mahou Sentai Magirenger) and Kouichi Sakamoto (Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers Turbo), Toei Company Board Director Shin-ichiro Shirakura, and critic-moderator Ryota Fujitsu formed a colorful team of veteran creatives on November 4 as they gathered at the 33rd Tokyo International Film Festival to discuss the enduring popularity of the Super Sentai genre in a master class entitled The History of Super Sentai.

Super Sentai, or “squadron,” refers to a brand of special-effects-driven, live-action television series (also known as tokusatsu) that feature young protagonists who use various devices to transform into a team of color-coded superheroes. Beginning with Gorenger in 1975, Toei Company has produced a new series featuring topical trends and popular young actors almost every year since.

When asked his thoughts on the success of Gorenger, Makoto – who played the Akarenger (Red Ranger) – said he initially believed, “Okay, I’m making a show to sell toys.” Makoto discussed the series’ humble origins, shooting in “the middle of nowhere” on a somberly quiet shoot. When the series began gaining popularity, the crew was stunned. “I was promised a year’s work, but was skeptical we would make it to six months,” he admitted. “It’s still a mystery to me.”

Makoto worked as an actor at Toei fortuitously. He had already received a job offer from a real estate company upon finishing university, but a Toei producer who frequented the restaurant he worked at part-time drunkenly told him to come work for him. “My feeling was that Toei employees were very frank and blunt despite being very well-educated elites,” he said.

Each of the participants discussed how they felt about the show when they watched it in real time as kids. Arakawa explained how the original show was like a “toy box,” embedded with a lot of fun ideas that were attractive to kids; while Watanabe detailed his Saturday evenings watching a slate of tokusatsu programs and creating comics out of the characters.

What makes Super Sentai special, according to Watanabe, is its invention within repetition: “There is a formula to it. There are always villains doing something bad, and the heroes always defeat them through teamwork. Sometimes the story gets complicated, but the principles of this formula must remain the same.” Added Arakawa: “The strangeness of the villains is certainly interesting, but the drama is created by the five ranger characters.”

The series was adapted for North American audiences in 1993 with Saban Entertainment’s Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers, casting American actors and actresses for the narrative portions, but recycling the special effects, acrobatic stunts and costumed fighting sequences from the Japanese TV shows.

Sakamoto was a stuntman and choreographer before being enlisted as an assistant director for the first Power Rangers series, and he soon became a director of subsequent series like Zeo, Turbo and Ninja Storm. While the show itself initially underwent severe localization for Western audiences, such as being much more conscious of diversity in the cast and stories, Sakamoto explained that they gradually adopted more Japanese characteristics from the original sentai shows as they began understanding more and more about them.

He also explained the many changes the staff had to make to the original series due to restrictions in US broadcasting laws and cultural customs: “Heroes can’t directly punch or shoot or stab the villains, so we would have to come up with acrobatic workarounds. For example, it was okay to make a villain fly back from the impact of a blocked attack.” Added Shirakura: “American superheroes also don’t have the custom of saying their name when they appear [like sentai heroes]. Superman doesn’t say ‘I’m Superman.’”

Shirakura has produced countless tokusatsu shows for Toei during a 27-year span, and he said the popularity of the series abroad was actually a challenging time for the company: “A lot of people internally tried to take credit for that success. We became a little complacent and forgot something important over those years. We had to ask ourselves: what worked so well in the US, and what has worked for so long in Japan? We wasted a good deal of time.”

Shirakura added that Super Sentai began losing popularity to another tokusatsu stalwart: “A popularity gap grew between Super Sentai and Kamen Rider in 2000. The staff of Kamen Rider doesn’t consider us rivals, but I’d like to strike back and make them consider us threats again.”

Toei produces their tokusatsu series in collaboration with toy company Bandai Namco, which designs products that are integrated into the narrative fabric and style of the episodes. The process is collaborative, with the ideas for new premises coming from both companies. As Shirakura explained, “We interview the salespeople and toymakers and ask them what they want to sell. Various people present ideas and there’s a back-and-forth process where we decide together.”

Sentai toys are marketed to boys, but in response to one audience question about women working in tokusatsu, Shirakura said that the industry was finally diversifying. “There are several female directors and writers of Sentai now, such as Fumi Arakawa and Junko Kobayashi, and we have female producers of Sentai series at Toei as well. We don’t think there’s anything especially gendered about Sentai and we’d be happy if this entire panel was comprised of female creators.”

Makoto concluded the lively master class with his wish for the future of Super Sentai: “I pray that we will have a coronavirus-free 50th or 60th year anniversary of Gorenger and Super Sentai in the future.”