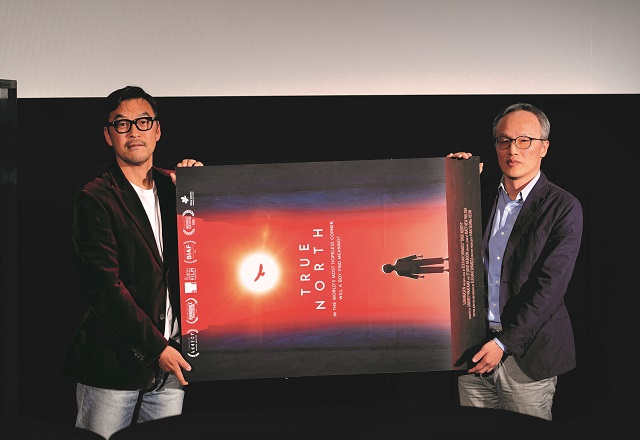

Writer-director Eiji Han Shimizu fielded questions on November 3 following the Japan premiere of his True North, an animated feature film playing in the World Focus section of the 33rd Tokyo International Film Festival.

A co-production between Japan and Indonesia, True North tells the story of Yo-han, a North Korean boy who is sent to a forced labor camp along with his mother and younger sister for the supposed political crimes of his father, who has disappeared. The camp becomes the new home and hell for Yo-han and his family for the next decade, with each day the same: the men work in coal mines satisfying quotas to avoid beatings, while the women farm the land and live in constant fear of being raped by prison guards. The prisoners are occasionally rounded up for “confessions,” where they accuse each other of crimes and where many are then sent to a cryptic place called the Total Control Zone, where guards torture their victims and work them literally to the bone.

Shimizu, a fourth-generation Korean-Japanese, created the story to bring awareness to the human rights abuses being perpetrated in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. His experience working on documentaries gave Shimizu the interviewing skills he needed to speak to a variety of witnesses: defectors to South Korea who had lived in the camps, ex-guards from the camps, women who had heard stories of the camps after moving to the DPRK, and family tales from his mother and neighbors of some 93,000 ethnic Koreans who had moved to the north as part of the “Paradise on Earth” program from 1959 to 1984.

The director discussed the difficulty in getting witness testimony due to North Korea’s system of kin punishment, or the “three generation” rule, where punishment is doled out not just to the offenders, but to their children and grandchildren. “The DPRK is very good at instilling a sense of collective responsibility,” Shimizu explained, “and this discourages a lot of would-be revolutionaries.”

The filmmakers’ research shows in the gruesome details of everyday life – meager rations of gruel, ramshackle living quarters, cardboard sheets as blankets, landscapes of grey and brown, a constant state of being monitored – and death, including the cases of illness, overwork, and malnourishment that so many of the prisoners eventually succumb to.

In this dystopic environment, Yo-han must choose whether or not he should compromise his values to protect his family. Shimizu was inspired by the book Man’s Search for Meaning by the psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, who wrote about his experiences in the concentration camps of Auschwitz and argued that what the survivors of the camps shared in common was their ability to quickly find a meaning for themselves.

Likewise, Yo-han’s journey to come to terms with his own purpose within unimaginable conditions provides much of the humanity of the film’s story. The small bursts of artistic expression – a makeshift instrument, a collective song, a decorated wall – that the prisoners create to make sense of their lives were inspired from testimonies of survivors. “I wanted to show how beauty could be found even in such tragedy,” Shimizu told the audience.

Growing up in Japan inspired him to use the country’s history and medium of anime to give “faces and backgrounds” to the headlines of North Korea’s human rights violations. While the filmmaking team utilizes computer-graphics animation, making it different from the cel-based style of contemporary anime, they intentionally avoided the smooth lines and textures of more polished animation studios. The characters retain some of the contours of their wireframe models, creating blocky forms akin to origami shapes.

“A smooth Pixar style works for films about princesses,” Shimizu said, “but it’s too shocking for a story about torture and concentration camps. We wanted to create a barrier between the style and the reality of the story.”

As the director makes clear, this is a human rights issue that is far from resolved: the political prison camps exist and are still in operation today, with an estimated 200,000 internees. The final shot of the film is a bird’s eye view of the prisoners looking towards the sky, evoking various satellite imagery of the camps that researchers and activists have uncovered and which are also displayed in the ending credits.

While not advocating a single solution, Shimizu explained that he does not want the story to end with his film: “That is the meaning of the final shot of the film. They are also looking at all of you, the free world. If you do not help these people, then no one can. So I would appreciate it if you could spread the word on this film.”