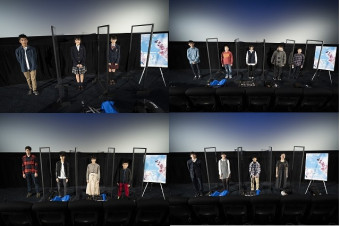

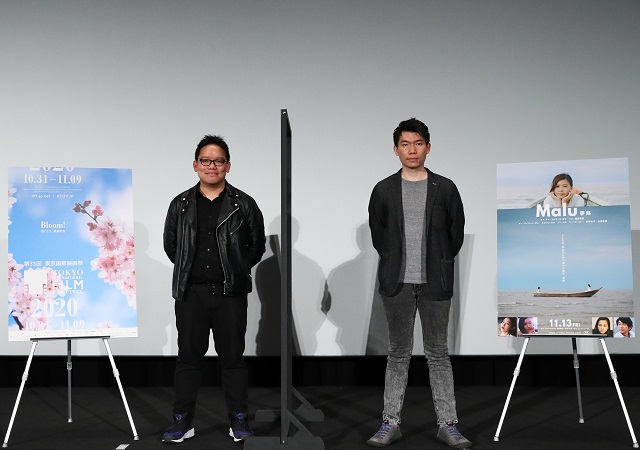

Director-writer-editor Edmund Yeo and cinematographer Kong Pahurak greeted the audience and fielded questions on November 5 after the world premiere of their poetic drama Malu, playing in the Tokyo Premiere 2020 section of the 33rd Tokyo International Film Festival. The winner of TIFF’s Best Director Award in 2017, as well as a graduate of Waseda University Graduate School, Yeo had gladly submitted to the required two-week quarantine so that he could be back among friends — making him one of only three non-Japanese directors who were able to attend the festival in person.

In the film, sisters Hong and Lan are separated at birth when Hong is kidnapped by her grandmother to protect her from her mentally unstable mother. Twenty years pass and Hong becomes a successful playwright while Lan stays at home to care for their ailing mother. The two reunite upon her death, but with no shared memories, there is no sibling spark left to rekindle. They once again go their separate ways, but a fateful occurrence pulls Hong back to Lan, who has moved to Tokyo and become a multilingual escort.

Malu means “shame” in Malay and “a day without horses” in Chinese, but, according to Yeo, was only decided as the film’s title a couple of months ago. He explained that the kanji characters which compose the words Japan and Malaysia are both contained in it too. The title is meant to be evocative and lonely, a play on words.”

The film is structured elliptically, fluidly cutting between different times and locations. The first half of the story switches back and forth between the childhood past and contemporary present of the sisters, with the mother as a sad and miserable presence throughout. The second half, like Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Millenium Mambo, focuses on Lan as she tries to find freedom and happiness in Japan, with unfortunate results.

Yeo told the audience he was inspired to structure the film unconventionally due to his interest in literature, which allows him to play with moods and explore characters freely from different points of view. The shift in perspective allowed him to show how the personalities of the sisters change: “Hong is very cold and unlikable in the beginning, but the second half shows her more pitiful and vulnerable. Lan, on the other hand, doesn’t talk and is more fragile, but when she goes to Japan, she’s more alive.”

The film shoot had an improvisational quality to it, with the actors contributing their own ideas to the characters. According to Yeo, MayJune Tan, who plays Hong, doesn’t smoke in real life, but “she wanted to do that for her character because the actress who plays her grandmother smokes in real life.”

Much of the film is told obliquely, without dialogue, but Pahurak’s cinematography conveys much of the interiority of the characters. “Film is interesting because you can communicate through expressions and movements,” the cinematographer explained. “We don’t really need dialogue and I think it’s more interesting that way.”

Pahurak’s images are accompanied by a haunting score from Shoplifters composer and Yellow Magic Orchestra luminary Haruomi Hosono, lending a mystical, spiritual atmosphere to the film’s landscapes. Yeo said he only provided minimal guidance for the music. “Hosono is a legend, so I didn’t give him too many instructions, maybe just one or two sentences about the mood of scenes. I didn’t want to restrict his creativity.”

According to Yeo, Japanese cinema was a strong influence on his depiction of the sibling relationship, from the middle-class female friends in Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Happy Hour to Sakura Ando’s character in Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Shoplifters, to the many films of Shunji Iwai.

Yeo was a big fan of anime and manga growing up, and also mentioned animation director Hayao Miyazaki as another major influence. “This is probably why most of my films have female protagonists,” he said. “I grew up watching Studio Ghibli films, which always have great female protagonists like Laputa, Nausicaa and Totoro.”

Both Yeo and Pahurak thanked their cast and crew in what was a “bittersweet” moment, since many of them were currently in Malaysia and could not attend in person due to the ongoing global pandemic. Movie theatres in Malaysia have suspended operations indefinitely, and cinema there is facing a precarious future.

Despite all this, Yeo offered words of encouragement: “We will overcome this challenge together and meet face to face soon. Even though they might not be here, despite the coronavirus, they are with us spiritually to see this film played in a cinema full of people. It’s very inspiring to see.”